Mariana Hernandez knew her son was struggling through the first year of COVID. His normally stellar grades had dropped to F’s, and he didn’t seem like himself.

But she wasn’t prepared for her quiet, bright child to ask, “If I wasn’t here, how would you feel, mami?”

Hernandez was used to taking action when her kids needed her — a few years earlier, when her children’s Detroit charter school was failing, she helped teachers unionize.

Now she was at a loss. “I didn’t know what to do,” she recalled. She reached out to one of her son’s former teachers, who referred her to a counseling center.

“You think your kid’s OK,” Hernandez said. “But then I talked with a psychologist and she said, ‘Actually, these are suicidal thoughts.’”

Two years of frustration, disruption, and loss have taken their toll on Michigan students, exacerbating a youth mental health crisis that has been building for more than a decade. Michiganders want schools to take action, polls show, and educators are stepping up to the challenge, drawing on research showing that emotional distress and student learning do not mix well. Michigan schools have no shortage of funds on hand, thanks to $6 billion in federal COVID relief, and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer is recommending a budget that includes an additional $361 million for student mental health.

Yet it’s not clear how far that money will go. Districts have hired social workers and counselors, selected new social-emotional learning curriculums, and purchased therapy dogs (see below for a detailed list). But students’ needs are immense, and the pandemic-roiled labor market is limiting districts’ efforts to hire additional staff.

At stake is the post-pandemic recovery of Michigan’s youngest citizens, not just emotionally but academically.

“We have kids that are chronically depressed and addicted,” said Paul Liabenow, executive director of the Michigan Elementary and Middle School Principals Association. “There is a massive backlog of need.”

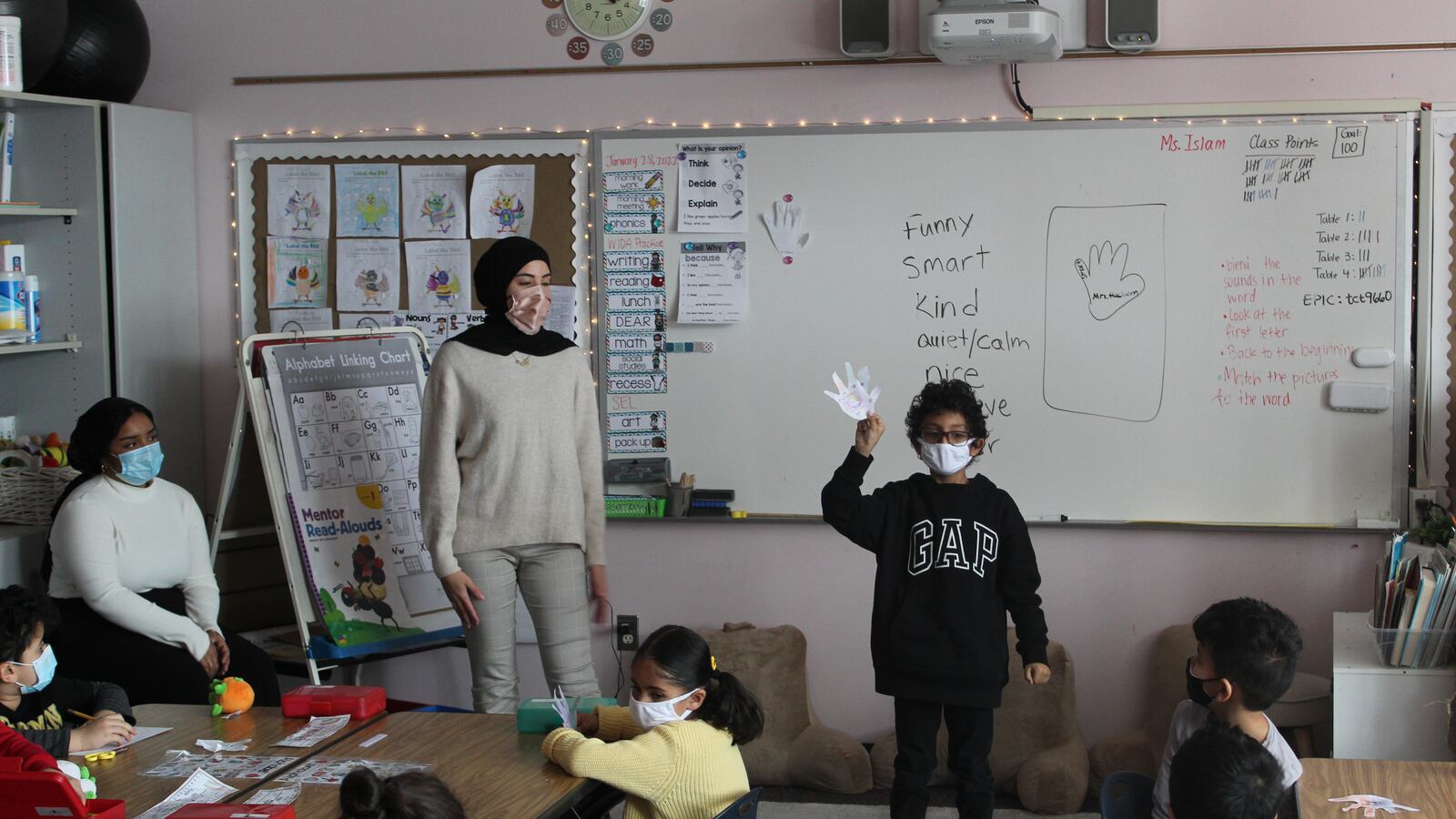

On a recent snowy Thursday, fifth graders at Becker Elementary in Dearborn lit up at the sight of Kawkab Hachem.

Hachem is the school social worker at Becker — and only at Becker.

Before the pandemic, Dearborn Public Schools social workers were assigned to several schools, moving between buildings to work only with the most severe needs. Now, with help from federal COVID funding, the district expanded its social work staff, and Hachem works full time at Becker. That means she’s gotten to know all 226 students at least a little bit, even as she spends focused time with certain students. And it means she has time to visit every classroom for weekly lessons on managing emotions, self-compassion, and connecting with peers.

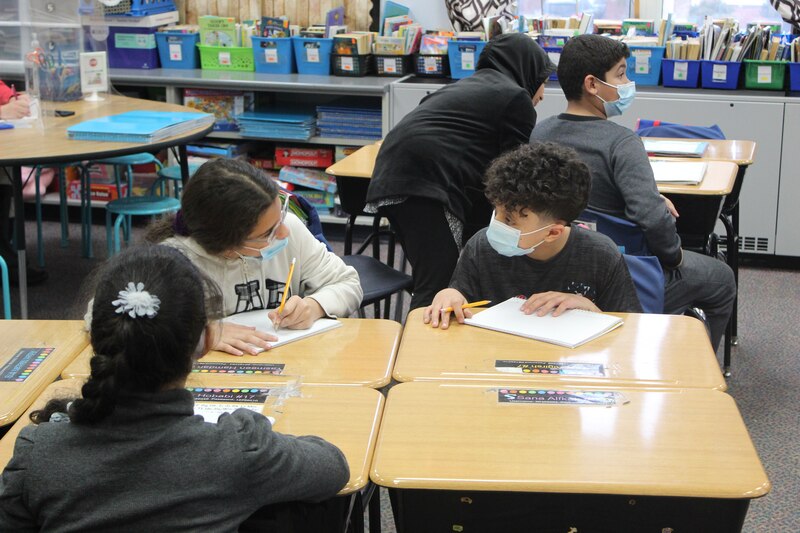

Nearly a year has passed since these fifth graders last had an online lesson. Kassem is an outgoing child who smiles behind his glasses as he talks. But his face darkens at the memory of sitting in his bedroom all day in front of a computer screen.

“Virtual learning made me so angry,” he said. “I felt like I was stuck.”

Today, though, Kassem and his classmates are making a list of 15 kind things students can do for another person. At another table, students are instructed to write kind notes to friends. “Dear Rached,” one student writes. “You are always there for me and you are the kindest person that I met in my life.”

Their teacher, Kristin Koss, has been with the Dearborn district for decades. In previous years, she said, social workers visited her classroom for social-emotional learning twice a year — not once a week.

“This is money well spent,” she said of the district’s new social worker hires. “The kids came back to the classroom (after virtual learning) and they didn’t know how to do school, they were so immature. These lessons help.”

Hachem’s presence also gives teachers space to focus on students with the most pressing academic needs — no small matter for teachers working to help students catch up from lost learning. While Hachem worked with the class, Koss pulled a single student aside to help him with a math concept he’d been struggling with.

At Kassem’s table, one of his neighbors, Mazen, agreed that lessons with Hachem are paying off.

“To care for other people, you have to care for yourself,” she said. “I learned that here.”

Michigan has taken notice of the mental health struggles of students like Khyiana Tate.

“Students — me included — we’ve been isolated, ” said Khyiana, a senior at the Michigan School for the Deaf. “I was stuck at home. A lot of times I was depressed. They don’t know what it’s like to have outside socializing just be snatched right from under us.”

For Tate, one solution is to hire more social workers and counselors.

Many Michiganders would agree. They put higher priority on addressing student mental health than almost anything else schools can do with federal COVID funds, according to a January poll conducted by Chalkbeat and the Detroit Free Press. Policymakers, too, have turned their focus to student mental health with budget proposals and efforts to revamp a health care system that lacks enough beds and providers to meet the needs of youth who are battling mental illness at growing rates.

Yet schools are struggling to find mental health workers to hire. The pandemic caused turmoil in labor markets, adding to a shortage of trained school social workers that began years before, said Kim Battjes, a professor at Michigan State University who trains school social workers. If districts can find someone to hire, Battjes said, they must often find ways to train them on the job.

“It’s like, ‘Yay, we’re getting money! Oh no, we don’t have people to fill these positions!’” she said. “School districts are hiring people who have never even worked with a kid a day in their life as therapists in schools.”

COVID funds alone won’t be enough to improve working conditions in schools, which have been deteriorating for years and making hiring more difficult, said Elizabeth Koschmann, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan and the director of TRAILS to Wellness, a nonprofit that shares research-based mental health practices with schools.

“The environment inside our schools is one of unimaginable stress, pressure, and relentless competing demands that all present as urgent priorities,” she said in an email. “And yet, the salaries for the staff remain largely the same. Burnout is driving staff away from the entire field of education and districts can’t find enough people willing to take open jobs.”

Surveys of parents and teachers in Coloma, a small town on the west side of the state, suggested that social and emotional health should be top priorities, echoing statewide poll results. But the district decided not to expand its staff of social workers, instead opting to purchase software that promotes social-emotional learning. District leaders were wary of funding the positions with one-time money, and they worried they couldn’t hire social workers if they tried.

“We didn’t try to allocate funds for social workers because we knew we couldn’t find them,” said Dave Ehlers, superintendent of Coloma Community Schools.

In Detroit, the district opted to contract out for additional mental health services rather than temporarily hire new counselors and social workers, said Superintendent Nikolai Vitti.

Dearborn, a large urban district bordering Detroit, took another path. The district hired new social workers using federal funds on the assumption that it won’t replace employees in other areas, if need be, as the funding runs out.

“A lot of how we look at funding is through attrition,” said David Mustonen, director of communications for Dearborn Public Schools. “Being a big district, we know we can lose anywhere from 80-100 instructional employees every year. It may mean we don’t replace a resource teacher, or maybe instead of four custodians in a building, there’s three.”

And that might not even be necessary, Mustonen said, if state funding for education rises, something Whitmer is proposing amid a historic budget surplus.

After asking her son’s former teacher for help, Hernandez found a therapist for her son at Southwest Counseling Solutions, a nonprofit in southwest Detroit, where she lives.

His depression has lifted somewhat, she said, and the suicidal thoughts stopped, though he felt anxious and isolated when his school in the Detroit Public Schools Community District reopened this fall.

“He has ups and downs, and the lows we have are still really low,” she said.

The episode left Hernandez with feelings of guilt. Was she prepared for something like this? Should she have noticed sooner how badly her son was struggling?

She said she would have benefited from training on how to recognize mental illness in a child. And she said she is glad that many districts, including in Detroit, are looking to expand their mental health staff.

School districts across Michigan are using COVID funds to do those things and more:

In response to the pandemic, the federal government poured a record amount of money into schools — $6 billion in Michigan alone. Chalkbeat, the Detroit Free Press, and Bridge Michigan are collaborating to track where the money is going and how it is helping students.

To report on how schools are using the money to support student mental health, we pored over state records showing how districts planned to spend their share.

- Lansing Public Schools is creating mental health programs with TRAILS to Wellness, a school-based program based at the University of Michigan. TRAILS provides brief lessons on mental health designed to be delivered to entire classes, student well-being surveys, mental health activities for staff, and suicide protocols.

- In Grand Blanc, a suburb of Flint, the school district plans to hire seven new staffers to work one-on-one with students on social and emotional issues — one for every two elementary buildings, one for each middle school, and one for the high school. Students will be selected to work with the new staffers based on a mental health assessment or referrals by an adult.

- The Kalamazoo district plans to pay 100 teachers an annual stipend to meet with small groups of students in advisory sessions that will focus on the challenges students are facing in life.

- In Grand Rapids, the district plans to cover the cost of additional social workers and therapists.

- Detroit Public Schools Community District will spend $10 million to contract with five organizations to provide mental health services, including therapy and diagnosis, to 3,700 Detroit students with the most severe mental health needs. The district expanded its full-time counseling staff in recent years, but demand for their services became overwhelming during the pandemic.

- In Battle Creek, the district plans to hire a student support coordinator, an administrator who will help schools develop plans to address severe mental health issues among students and work with community agencies to connect students to mental health services outside of school.

- In Flint, the city district contracted with a behavior specialist to address student trauma when classrooms reopened. When classes were virtual, the district hired a social-emotional learning coordinator to work with 9-12 graders who were learning online during the 2020-21 school year.

- In Plainwell, near Kalamazoo, teachers, social workers, and other staffers are set to review district curriculums to bring social-emotional learning into academic lessons. For instance, a math teacher might include instruction on coping with frustration or working with partners to solve challenging problems.

- Chatfield School, in rural southeast Michigan, hired an outside firm to provide mental health workshops to parents, students, and staff.

- North Huron Schools, a small rural district in eastern Michigan, purchased a therapy dog named Chipper who lives with a teacher and spends his days at school. Teachers can refer distressed students to spend time with Chipper.

At the same time, Michigan has a massive budget surplus. With student activists calling for expanded mental health services in the wake of the school shooting in Oxford, Whitmer is calling for the state to invest an additional $361 million in student mental health. That proposal will likely be challenged by the Republican legislature, which proposes spending the surplus on a tax cut.

Still, these new investments may not be able to keep up with the need for mental health services. Consider the Grand Haven School District in western Michigan, where a string of six suicides between 2011 and 2017 spurred district leaders to expand their mental health staff to the levels that many other districts are trying to reach today.

Even as other districts in the area struggle to hire mental health workers, Grand Haven’s larger staff is struggling to keep up with mental health needs.

“We’re seeing the trickle effects of the constant chaos and uncertainty of the pandemic,” said Katie Havey, a district social worker. “We’re seeing more kids needing major interventions. We’re doing more suicide screenings and seeing higher levels of threat assessments.

“It is crazy to reflect on all of these things that we’re doing really well and realize that we could still use so much more support.”

Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 schools and early childhood education. Contact Koby at klevin@Chalkbeat.org.