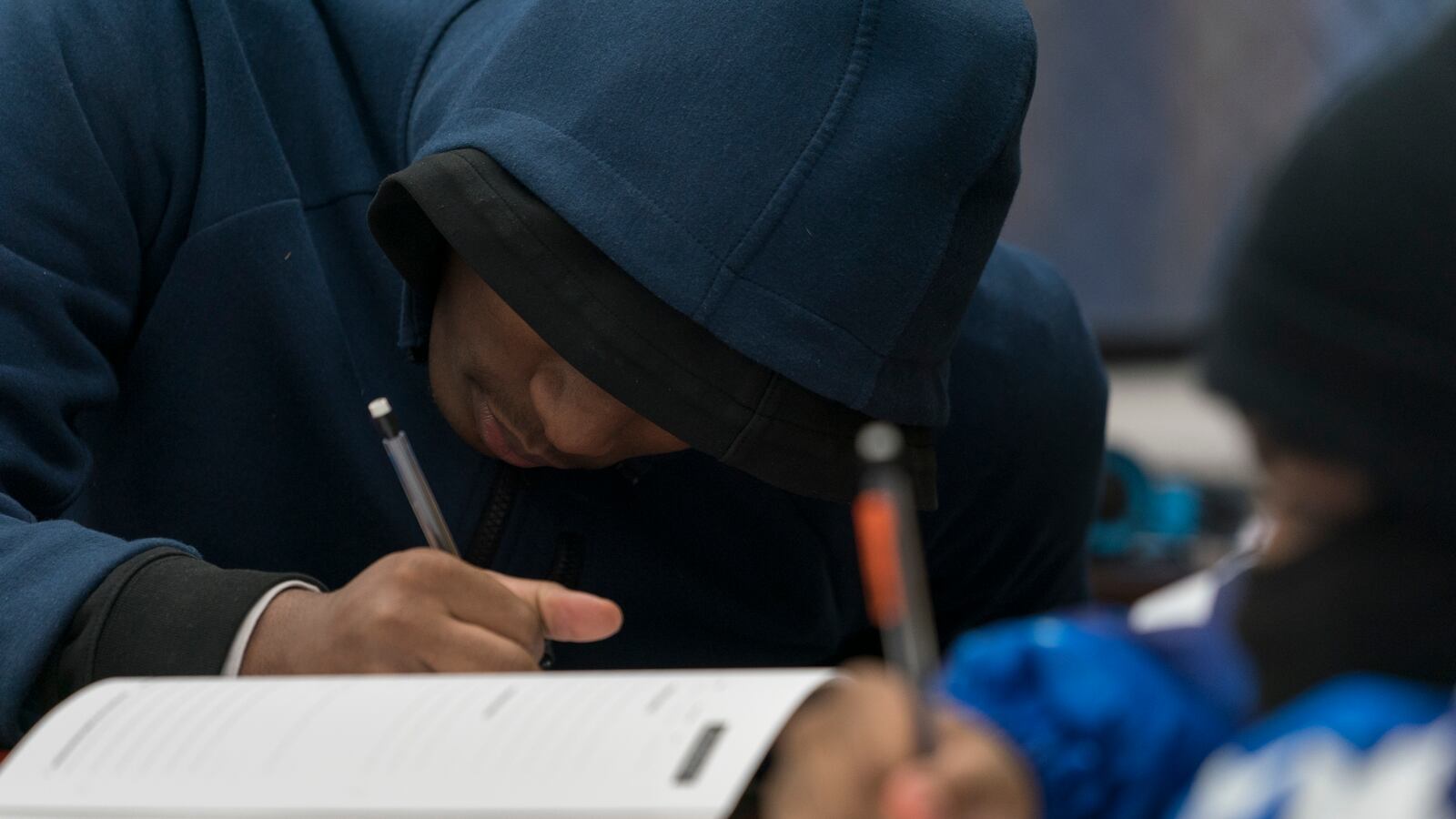

William Wheeler was working his way through a phonics exercise with his tutor on a rainy Thursday morning.

“Night. Coupon. Disease,” William said out loud, reading from a list of words as his tutor, Erica McLemore, looked on in a classroom at Osborn High School in Detroit.

By the end of the minute-long exercise, William had run through a long list of words three times, reading nearly all of them with precision and faltering only once, for a split second, on the “ow” sound of the word “ouster.”

When he was done, he high-fived McLemore.

William, a sophomore, wasn’t always so confident. A year ago, he shied away from reading out loud in class, fearing he “was going to mess up.”

That was before he began working with McLemore five days a week, through a nonprofit organization called Beyond Basics, which has provided tutoring in Detroit schools for more than two decades. The tutoring has given William strategies to use to make “big” or multisyllable words easier to decipher.

“I’m not afraid to sound out a word,” he said. “I’ve improved. Everything I do here, I try to use in my other classes.”

The work students like William are doing with tutors is critical to recovery efforts in the Detroit Public Schools Community District, which was struggling academically before the pandemic, and has seen failure rates rise since.

Like many other districts across the U.S., DPSCD is investing heavily in literacy tutoring, in part using federal COVID relief dollars — the district received nearly $1.3 billion — to provide intervention to students who are two or more grade levels behind.

Tutoring has proven to be one of the most effective ways to catch students up, and the Detroit district appears to be doing much of what experts say is critical to the success of such programs, including providing tutoring during the school day, at least three days a week, in small groups, and with well-trained tutors.

That’s despite a lack of leadership or guidance from the state, and it contrasts with other school-based tutoring programs around Michigan that are hampered by poor coordination, resource shortages, and divergence from best practices.

In August, the district’s school board approved a contract with Beyond Basics for between $9.9 million and $12.62 million. Much of that will be covered by federal COVID relief dollars, as well as money the district received through the settlement of a federal “right to read” lawsuit.

Under federal rules, some of the contracted amount — $2.1 million — will go toward serving private school students in the city.

Beyond Basics had been serving 300 students annually in district high schools prior to the pandemic. The contract calls for the Southfield-based organization to scale up its operations over two years to serve 1,500 students.

In June, the district awarded a nearly $1 million contract to Brainspring, a company that is providing literacy intervention for students in grades K-3 as well as students attending the district’s virtual school.

Meanwhile, the district has continued efforts that were underway before the pandemic, such as using academic interventionists to help struggling students. And a volunteer program the district created with longtime community activist Helen Moore, called Let’s Read, is also connecting adults in the community who help K-3 students with reading.

Moore, who has advocated on behalf of Detroit children for decades, said the extra help is sorely needed.

“The kids are even farther behind than they were before the virus,” Moore said. “If you sit in the room with the children as they read … you almost cry because they are so far behind.”

Finding a solution to student literacy woes

Many districts, including Detroit, faced profound challenges after the pandemic disrupted education in March of 2020, forcing schools to shut down with little preparation. While some wealthier communities were able to quickly pivot to online instruction, it took weeks for that to happen in the city, largely because so many homes didn’t have adequate technology.

The following school year saw most Detroit students still learning online, but the extended remote-learning experience was ineffective for most students here and elsewhere in the country, and left schools grappling with learning losses.

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said the number of students in the district who are now two or more grade levels behind is on the rise. That’s a big setback for a district that was starting to see a small improvement in test scores before the pandemic. Worse, the poor test results are coinciding with an increase in chronic absenteeism.

“If students are frequently absent, then that negates the literacy intervention impact we can make,” he said.

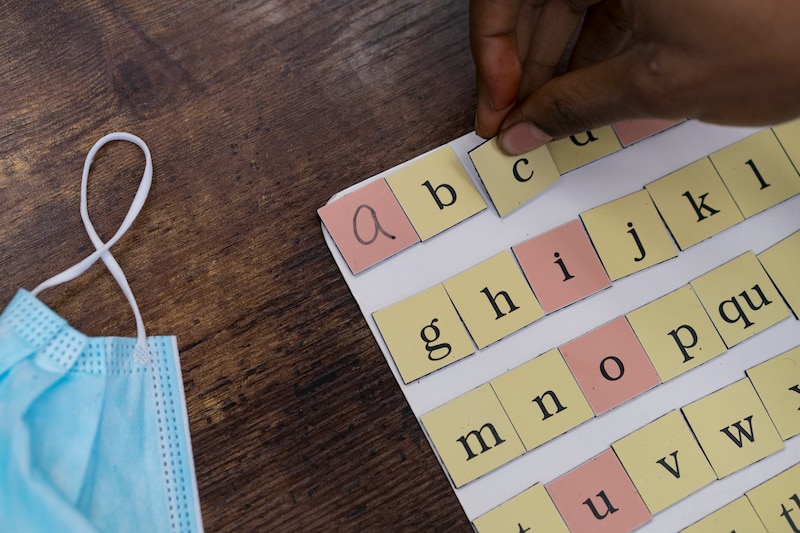

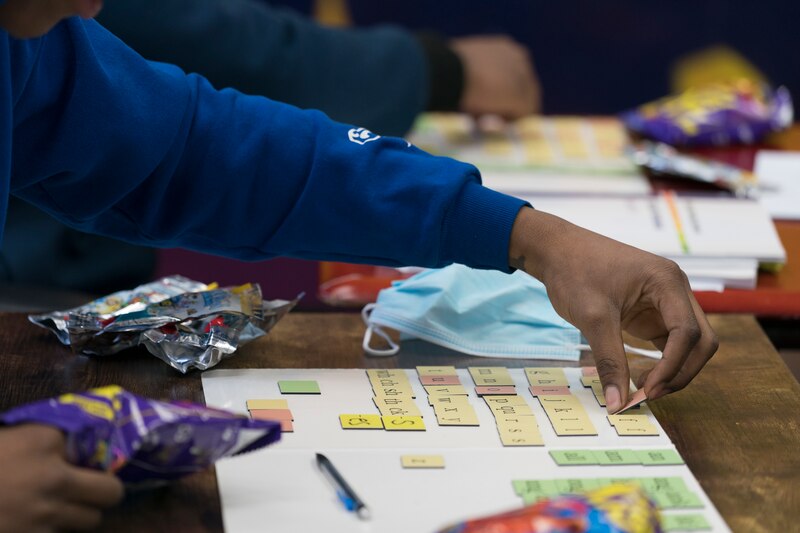

He said the district has turned to organizations like Beyond Basics and Brainspring because they have a track record for improving literacy, and because their programs use Orton-Gillingham, a multi-sensory, structured literacy approach. School districts have increasingly adopted literacy approaches such as Orton-Gillingham because they tend to work for students with dyslexia or other reading problems, and emphasize a carefully sequenced approach to reading instruction, including phonics.

Beyond Basics officially launched in 2002, with a focus on reducing gaps in learning between city and suburban children.

Pamela Good, the organization’s co-founder and director, describes youth illiteracy as an “epidemic” that should warrant more national attention.

“Without being able to read you cannot really plug into society,” said Good. “If you graduate (without) being able to read, there really isn’t a place where you’re going to get that intensive intervention.”

The Beyond Basics program aims to improve students’ reading level by two grades in the span of six to 10 weeks. Its approach has evolved over the years to adopt the Orton-Gillingham method and shift from using volunteers to paid tutors trained in that method.

The organization has long had a business relationship with the district. There’s also a family connection: Vitti’s wife, longtime literacy advocate Rachel Vitti, is a director at Beyond Basics and has been an employee of the organization for two years. The connection was disclosed to the Detroit school board as it considered the contract.

Board member Sherry Gay-Dagnogo said Rachel Vitti’s employment at Beyond Basics “didn’t jump out at me initially” in the materials the board reviewed.

“I did learn of it afterwards,” Gay-Dagnogo said. “But I felt that there was some measure of separation, the way it was conveyed. But be that as it may, I could see how that could be considered a conflict.”

Still, she said Beyond Basics’ track record was the reason she voted for the contract.

“Anytime you’re seeing the level of literacy challenges that we’re having … if this is a company that is capable and has demonstrated the ability to advance and scale its work, then certainly we want to be supportive in that regard,” she said. “That was my rationale.”

Angelique Peterson-Mayberry, the board president, expressed similar feelings about the company’s track record, and added that the district will be using literacy growth data to evaluate the company’s progress.

“The Board made a decision based on who could deliver the needed services at scale and did so with full transparency,” Peterson-Mayberry said.

Vitti told Chalkbeat last week that he recommended Beyond Basics for the contract based on its long track record in the district, not his wife’s employment there. The group had previously provided tutors to the district using philanthropic dollars.

Vitti said the district was expanding its work with Beyond Basics before his wife joined the organization. And he said the organization “has demonstrated very clear results.”

For example, he said, 300 students received tutoring from Beyond Basics during the last semester of the last school year, and the average student demonstrated 1½ years of growth in literacy after a semester of the intervention. During the first semester of the current school year, the average student gained 1.8 years.

Beyond Basics’ own research suggests its program helps students see significant gains in four to 14 weeks.

Vitti attributed the program’s success to the Orton-Gillingham approach as well as strong training for tutors.

The program, though, is expensive.

The district’s contract with Beyond Basics will pay for 300 literacy tutors to serve 1,500 10th and 11th grade students.

“Unfortunately, many students need this type of tutoring but their families cannot afford it,” Vitti said. “Middle- and upper-middle-class families pay for it privately, and school systems are just now talking about it, but not implementing it.”

Tutoring programs offer needed one-on-one relationships

At Osborn High School in northeast Detroit, 50 students are participating in Beyond Basics, with the tutoring taking place daily in a classroom across the hall from the main office.

Principal Jamita Lewis says the individualized tutoring is “making an impact,” which she hopes will be evident in their performance on spring exams.

Beyond the impact on reading skills, Lewis said, “the students get mentoring, they get some leadership development, they have these one-on-one relationships.”

“I’ve never seen it anywhere where you have one-on-one tutors as part of a student’s schedule, where they’re in the school, giving that live, authentic help in real time,” Lewis said. “It’s not simulated on a computer.”

Tutoring is essential at a school like Osborn, where just 6.3% of the students were proficient in reading and writing on the SAT exam given the year before the pandemic. A pattern of such deficiencies across the district were at the heart of the 2016 “right to read” lawsuit filed by seven families alleging the state didn’t provide a basic education to Detroit students. Osborn received some of the money from a 2020 settlement of the lawsuit with the state.

The infusion of federal COVID relief money gives more Detroit schools an opportunity to benefit from programs to boost literacy. Tutoring has been spotlighted as a top priority for school districts seeking to use their federal investment to address learning loss.

Growing research suggests high dosage tutoring — defined as one-on-one or small group tutoring at least three times a week — is effective and improves academic performance.

Even under short time spans, districts like Detroit attempting to scale up tutoring to more students could see success, said Beth Schueler, a University of Virginia professor who co-authored a policy brief examining best practices for student tutoring.

Accelerated tutoring, even under a tight timeframe, Schueler said, has the potential to “make some pretty important gains.” And if the program proves successful and popular, she added, it could help make the case for a more sustained investment in tutoring, after the federal help expires.

That’s a nagging concern for Vitti.

In any other year, he said, the Detroit school district would have limited funding to employ academic interventionists to work directly with students in grades K-8.

“It will be difficult to sustain the amount of funding for this beyond next year,” he said.

So as the school year winds down, tutors and students must make the most of the time they have.

William, the Osborn sophomore, said his biggest goal this semester is to work on his reading fluency. Before the hour-long session wrapped up, he asked Marketia White, the Beyond Basics program manager at Osborn, for one last word to test him out. This time it was a polysyllabic word: “maladjustment.” William paused for a couple of seconds, while White encouraged him to remember how to break it down.

“Start from the end and work your way back,” White said.

William looked for the base word, “adjust,” and the suffix “-ment.”

“Ment. Just. Ah. OK … Mal … adjustment,” he said. He looked back at White for confirmation and grinned.

“See? Like magic.”

Ethan Bakuli is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering Detroit Public Schools Community District. Contact Ethan at ebakuli@chalkbeat.org.

Correction: June 15, 2022: This story has been updated to correct the amount of the contract with Beyond Basics, and the timing of the approval.