Sign up for Chalkbeat Detroit’s free daily newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system and Michigan education policy.

As federal COVID relief dollars for education begin to run out, school systems across the country are facing a jolt to their finances. But the Detroit Public Schools Community District has fared better than many in limiting the impact of the funding loss.

The district hasn’t been immune to cuts: Hundreds of positions were eliminated, the community has criticized district decisions, and parents remain concerned about the loss of some programs. But it deliberately focused most of the $1.27 billion it received from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief, or ESSER, on one-time costs — rather than recurring budget items that can’t be sustained without federal aid.

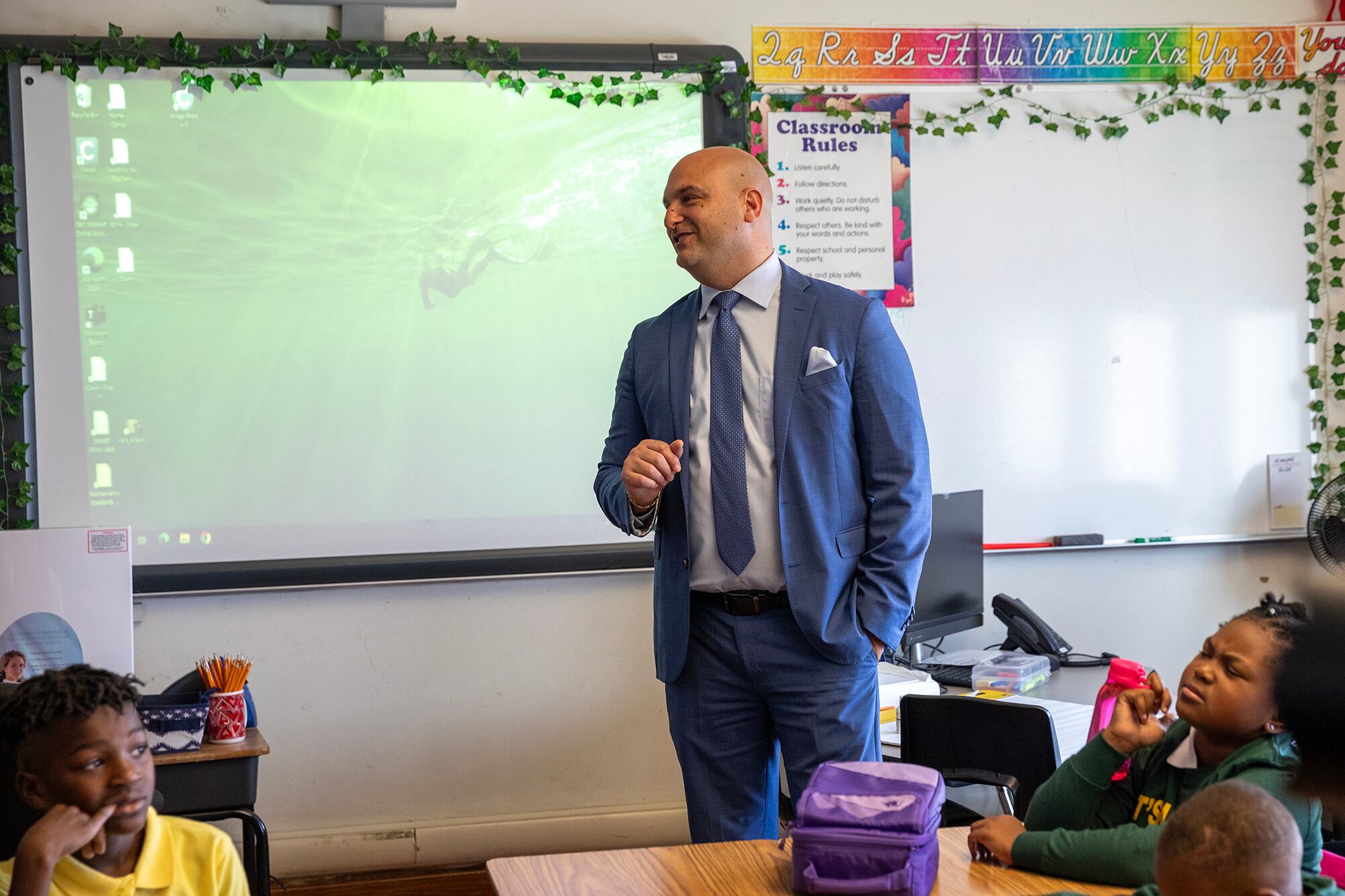

That strategy will save the district from a so-called funding cliff that many other school leaders may soon face when the federal dollars run out in September 2024, Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said in an interview with Chalkbeat.

Vitti talked about what he thinks the district did right and his recommendations for other school leaders.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What was the district’s strategy as you planned for the loss of the federal COVID relief money? What did you prioritize?

One thing that I’ve tried to do as superintendent is be disciplined with finances. … I always think about recurring revenue with recurring expenditures, and one-time revenue with one-time expenditures.

Boards, in particular, can be very vulnerable to spending one-time funding in a recurring way. Because of the concentrated poverty that our families face, you look at our outdated infrastructure, salaries that are not fully competitive, the wraparound services that our kids need — and all of that was magnified and exacerbated because of the pandemic.

So the normal challenges that we have as a district linked to concentrated poverty, linked to historic racism, you see that money and it’s like, “Wow, we can solve a lot of our problems,” because we’ve been talking about the need for revenue, because our kids need more than the average student.

When we paid for things that needed more people, we tried to rely on contracted services rather than increasing employment.

One focus of the dollars was let’s fill the revenue gap because of the loss of enrollment. Right when the pandemic hit and the first year we came back, we were down about 3,000 students. We’ve picked up some since.

(We kept everyone employed) that normally would have been laid off. You know, let’s not close schools, let’s not cut programming — that’s the last thing we want to do during the middle of the pandemic.

We funded things that were very specific to COVID, like masks, temperature check machines, ventilation systems, COVID testing, moving to smaller class sizes in order to have social distancing, the virtual school, nurses in every school, expanding mental health in all schools — we did all of that through contracted services, or it was one-time. There were things we did that weren’t linked to contracted services like expanding summer school.

About half of the dollars went to fund facilities, which was a clear one-time expense, one-time need, and an enormous gap in our district, which is that we have a $2 billion infrastructure problem with no revenue to solve.

There is a way to use the money to, for example, increase salaries, but you have to do it through bonuses if you’re going to be responsible. If you link it to salary increases, you’re going to hit a cliff.

Was getting kids back into classrooms in person with things like smaller class sizes, masks, hazard pay for teachers, and upgrading HVAC systems a focus to improve academic outcomes in the long run?

I think if we go back to the pandemic, the greatest sense of urgency I had was to get kids back in school, without a doubt. That literally kept me up at night and led to my own mental health issues. I did deal with mental health issues, because I didn’t feel like we were serving children the way they needed to be served. … Our children in particular needed in-person learning in order to continue to show the improvement we were definitely showing before the pandemic. I knew every day they were at home, we were getting farther behind.

2021-22 was the first year that everyone tested on M-STEP, and we really saw the impact of the pandemic that year. But in 2021-22, DPSCD showed less learning loss on average than the state of Michigan and less learning loss than city charter schools. That showed me that having this urgency of getting back in person and keeping schools open in that 2020-21 year was important (along with) fully implementing our curriculum online.

Which cuts were the most difficult to make, and which programs do you wish could continue but had to end due to the end of ESSER funding?

I never want to be the superintendent that has to reduce staff to get to a number, because I understand that there’s a human being behind it, and that human being is connected to a family. It’s never easy for me.

The next hardest decision probably came to not having summer school at the scale that we had before.

We heard from some parents and students that the loss of college transition advisers is disappointing. Do you wish the district could keep those positions?

What we said was, we have to protect direct impact on student achievement, so we definitely protected the classroom. We didn’t increase class sizes. We definitely have invested in our academic interventionists and even expanded them.

When looking at the college transition advisers, there’s no question they had an impact on children — no doubt about that — but not a direct impact on student achievement.

What we tried to do was convince college transition advisers to go into the On the Rise Academy program and become counselors, because that was something we could see expanding in future years, maybe with more (state money for at-risk students).

Did you anticipate the amount of criticism from the community you received about the cuts? Has it been difficult to communicate to the community that the end of some of the programs and resources funded by ESSER was due to the federal relief money expiring?

Detroit children have great need, and the school system in and of itself does not provide the resources that children deserve to be competitive with their peers in more affluent neighborhoods and school districts. That’s not a function of an incompetent, corrupt school board or superintendent. It’s the nature of how the schools are funded.

Although Gov. Whitmer has made strides in narrowing the gap between wealthy districts and DPSCD, the gap is still there. We not are not even equal yet. We are definitely not equitable.

People are very passionate about what we should be doing for our children. And there’s a sense of anger because our families know our children are capable.

What do you think other districts need to consider as they get to the point DPSCD reached last school year with the remainder of ESSER money being earmarked? What should they prioritize as those dollars run out?

My recommendation is to communicate often, frequently, and honestly about the advantages and disadvantages of the funding, and be upfront about how you’re spending the money.

DPSCD had less learning loss than our counterparts. And as we move into the 2023-24 school year, undoubtedly we’re narrowing the gap in performance, which means not only did we use the money effectively, we used it efficiently.

Hannah Dellinger is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 education. Contact Hannah at hdellinger@chalkbeat.org.