Test scores aren’t the only factor that parents consider when they take advantage of Michigan’s school choice policies. They also want to live near their children’s schools.

That’s a finding of new research on school choice in Michigan. While seemingly obvious, the conclusion adds evidence to a long-running policy debate in Michigan, which has robust school choice policies but few rules to ensure that students have school options in their own neighborhoods.

Researchers Danielle Sanderson Edwards and Joshua Cowen used six years of student address data from 2012-13, tracking residential moves for every student in the state who either attended a charter school or a school outside their own district via Michigan’s “schools of choice” policy. The study was funded by the National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice, an initiative of the U.S. Department of Education.

More than one-fifth of Michigan’s 1.4 million students choose to attend a public school not assigned to them.

Michigan allows students to enroll in a school district even if they don’t live within that district’s boundaries, provided that the receiving district agrees to accept students through the state’s interdistrict choice program.

Students can also pass on their local school and enroll in charter schools, publicly funded schools that, in Michigan, are typically run by for-profit management companies and aren’t controlled by an elected school board.

Among the study’s key findings:

- Half of families who left schools of choice programs in Michigan did so because they had moved into the district they were already attending.

- Families that had longer commutes to their chosen school were more likely to exit school choice programs compared with those whose school choices did not lead to longer commutes.

- Students who moved residences were more likely to exit school choice programs and attend their local school district instead.

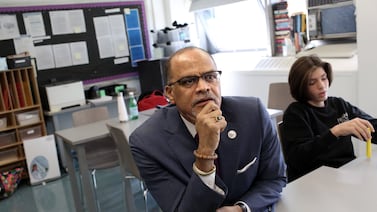

“Guess what, parents want their kids to go to school near where they live,” said Cowen, a professor at Michigan State. “Next to a school’s academics, distance is by far the biggest thing for parents. The longer your commute time, the less likely you are to stay in that school.”

Advocates of school choice have long framed Michigan policies as a way to help students whose neighborhood schools are struggling.

“All the work I’ve done has been to help kids for whom the schools they’re assigned don’t work,” said former U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos in 2017. In 2016, DeVos led a successful push to block legislation that would have given the city of Detroit more control over where schools were located in the city, a change that advocates hoped would, among other things, reduce commute times for families.

Cowen said the data shows that narrow, choice-focused policymaking ignores families’ broader needs, such as proximity to school.

The data “is taking issue with this general sense that school choice is the cure-all,” Cowen said.

Indeed, educators have argued for years that school choice policies destabilize schools by encouraging families to frequently change districts.

“We have created a culture where a parent gets angry at a school or doesn’t like what we do, they take their child and they go to another school which is absolutely detrimental to children,” said Christina Gibson, superintendent of Eastpointe Community Schools, during a panel discussion last week. About 25% of students in her district are enrolled through schools of choice.

But the data suggests that schools of choice may also be a pathway to stability for families. Cowen said that findings indicate that families use schools of choice to enroll their children and secure a place in a district where they can’t yet afford housing, then move into that district later on.

Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 schools and early childhood education. Contact Koby at klevin@chalkbeat.org.