Michigan teachers spent less time giving reading lessons during the pandemic. During the same period, half of all third graders in the state were identified at some point by their teachers as needing extra help with reading.

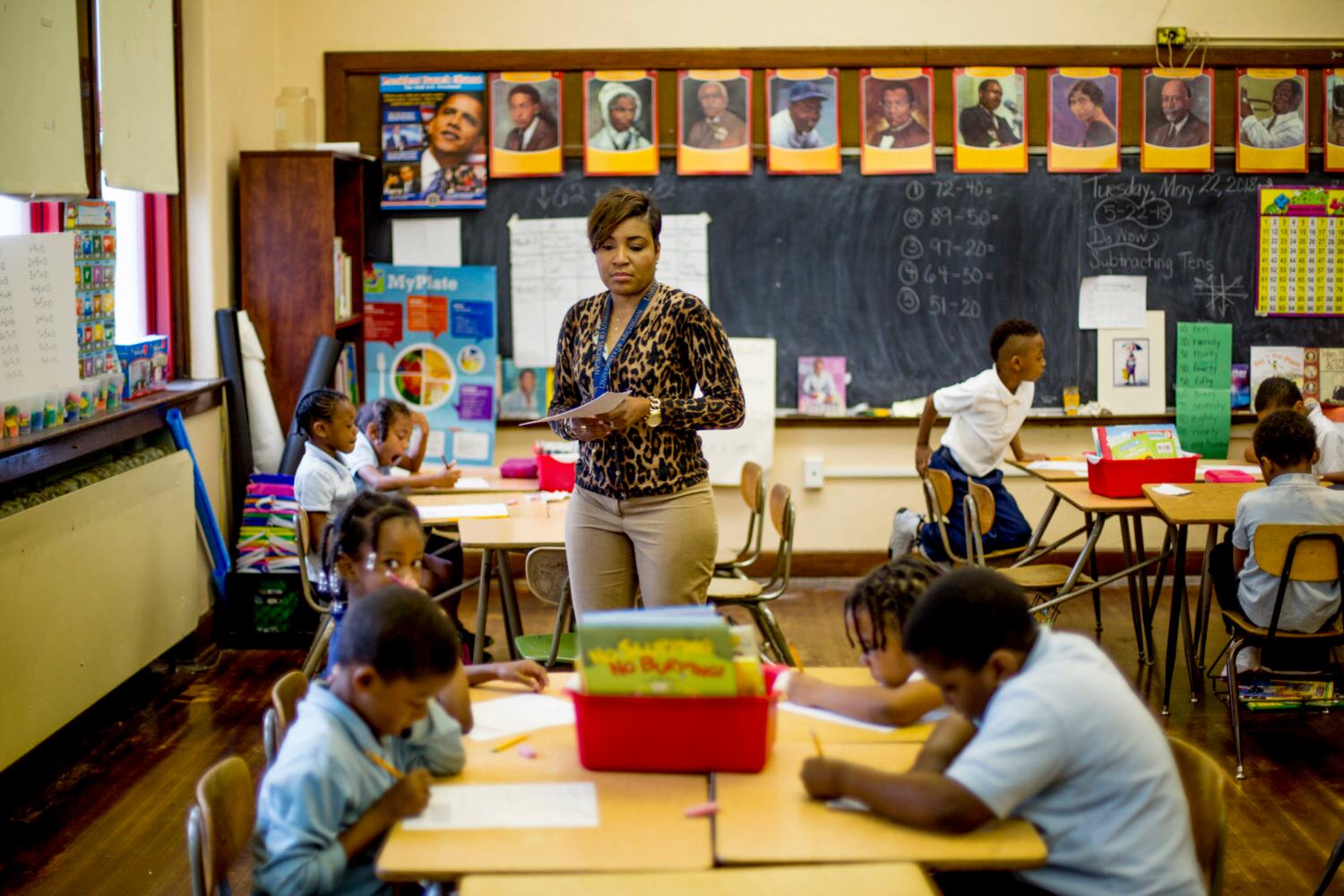

Those findings from a new report on Michigan’s third-grade reading law underscore the academic toll of the pandemic — especially for students from low income families and students of color, who were more likely to learn virtually last year. Michigan legislators passed the law in 2016 in an effort to reverse years of backsliding reading scores. It increases the number of coaches working with teachers to improve reading instruction, while threatening to hold back third-graders with especially low reading scores.

While earlier reports suggested that the law was having a modest positive effect, the latest data suggest that there is a long road ahead.

Students from low income families, who speak English as a second language, and students of color in particular, got less literacy instruction last year, according to the report, because their districts were more likely to be operating fully online.

“It’s an equity issue,” said Katharine Strunk, a co-author of the report. “If those students are receiving even less instruction time, the gaps are going to get bigger.”

Experts are calling on schools to use federal COVID funds to bolster students’ reading skills through tutoring, teacher training, and summer school programs. While many districts are already putting those programs in place, the pandemic continues to disrupt education across the state.

Researchers at Michigan State University drew on surveys and test score data to track student progress since the passage of the third-grade reading law. The controversial retention portion of the law, which requires schools to hold back third-graders with especially low English scores, was paused in 2019-20 due to the pandemic.

Key points of the 194-page report, include:

- In a survey of nearly 7,000 Michigan teachers, many said they spent less time teaching reading last year compared with the year before. The same held true in other subjects. Among educators who taught virtually, 40% said their literacy instruction time decreased.

- Half of 2020-21 third graders were listed as “reading deficient” by their school districts at some point in grades one through three. While it’s up to individual districts to define what this means, all students who receive this label are eligible for extra instruction and support in reading.

- Teacher coaches reported that they spent less time helping teachers improve their literacy instruction during the pandemic.

- While 5% of students scored low enough in 2020-21 to be held back, districts intended to hold back just 0.3% of all students.

Statewide, English test scores fell last year, but researchers did not include that data in the report, noting that less than three-quarters of students in the state had taken the M-STEP exam amid the pandemic.

The MSU Education Policy Innovation Collaborative, the group contracted by the state to study the third-grade reading law, plans to release a separate report measuring students’ progress in literacy using benchmark tests taken this fall. Benchmark tests are given by individual districts to track students’ progress throughout the year.

Michigan still is not doing enough to support student literacy, said Jennifer Mrozowski, director of communications for EdTrust Midwest, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“This report reinforces what we have long seen: Michigan is missing the mark in strategically improving early literacy, and there are disproportionate gaps in opportunity for the state’s most disadvantaged students,” she said in a statement.