With elections that could alter the state’s political balance, a new agency getting involved in education issues, debates over funding and budgets, and numerous policy changes taking effect, 2024 will be an eventful year for education in Michigan.

Educators and advocates who recorded big victories for their reform agenda in 2023 will look to keep their momentum in 2024 and tackle what they see as some unfinished business — specifically, dealing with staffing needs and locking in more equitable and sustainable funding for public schools.

But they face a number of obstacles and uncertainties, including the potential for economic and political shifts.

“I think a lot of us will be looking at the budget in 2024,” said Bob McCann, executive director of the K-12 Alliance of Michigan, which advocates for public schools. “We put really good building blocks in place in 2023. But can we find a long-term, sustainable solution for funding?”

“When looking at things like social workers, we can’t make the hires we need without knowing there is long-term funding in place,” McCann added. “We need to find ways to make sure these programs will be funded, even in leaner budget years. Those are the critical next steps.”

Wendy Zdeb, executive director of the Michigan Association of Secondary School Principals, said it’s essential that reasonable increases in per-pupil funding continue.

“It will depend on state revenue and the economy, so it’s hard to say what it will look like moving forward,” she said. “I’m hopeful about where we’re at now and that it is only going to increase. But history tells us otherwise, and that’s always concerning.”

Here is a preview of some of the top stories Chalkbeat Detroit will be watching in 2024.

School funding: The push for equity continues

The end of federal COVID relief aid for education has increased the pressure on school district finances this year and reignited the conversation about equity in school funding.

Michigan has historically been among the worst states in the nation for big gaps in school funding between wealthy and impoverished communities. Educators and advocates have criticized the state’s current method of funding schools for decades and pushed for an overhaul of the system.

Last year, the state passed a historic $21.5 billion school aid budget that provided gains for the students with the most needs. An “opportunity index” measure in the budget allocates more weighted funding to districts with higher concentrations of poverty. Previously, the state gave the same amount of per-pupil dollars to all students considered to be at risk, regardless of the poverty levels in their districts.

Advocates say this type of funding boost would have to continue for decades in order to correct imbalances for districts that historically were underfunded.

2024 elections: Fate of Whitmer’s agenda at stake

Just over a year ago, Democrats solidified their power in Michigan by retaining the governor’s office and winning control of both chambers of the Legislature by slim margins. As a result, a number of education policy changes and priorities they fought years for became a reality in 2023.

This year’s elections will test the Democrats’ strength. Already, their legislative power is diminished: Two Democratic House members won mayoral races at the end of 2023, and their departure leaves the House with a 54-54 partisan split, at least until new members are chosen in an April 16 special election.

Both seats are in heavily Democratic districts. But given the stakes of the election — potential control of the House and the power to advance or thwart Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s agenda — political analysts are waiting to see if Republicans will make an aggressive push to flip the seats in their favor. A total of 12 candidates have filed to run in a Jan. 30 primary for those seats.

Another test will come in the November general election, when the entire House will be up for election.

The Detroit Public Schools Community District will have contests for three school board seats in November, with the potential to alter the dynamic of the seven-seat board.

The Michigan State Board of Education will also have seats up for grabs in 2024, and other potential changes tied to the elections. The only two Republican-held seats on the board are up for election, and Republicans will likely fight hard to keep them.

One of the Republican members, Nikki Snyder, is currently campaigning in the Aug. 5 Republican primary for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Sen. Debbie Stabenbow. And Board President Pamela Pugh, a Democrat whose term expires at the start of 2031, said she plans to run for an open U.S. House seat in 2024.

Candidates for the board are typically announced at party nominating conventions, usually in the summer. The primary elections for the U.S. House and Senate seats will be Aug. 6.

Of course, 2024 is also a presidential election year, and debates over school choice, teacher pay, student mental health, and curriculum have already begun to play out in the campaigns ahead of primary contests beginning this month. Candidates vying for the Republican nomination have also made an issue of learning materials and library books containing mentions of racism as well as sexuality, gender, and LGBTQ+ matters.

Student health: Bills and health centers in the works

Amid the continuing recovery from the pandemic, more legislators from both parties are acknowledging the mental health struggles students are experiencing, and they’re supporting bills to improve access to mental health services. Several more bills were introduced in 2023 and we expect to see movement on them in 2024.

One bill would allow K-12 public school students to take up to five mental-health days a school year as excused absences. State Sen. Sarah Anthony, a Democrat from Lansing who introduced the bill, said she will advocate for it to move quickly through the education committee when the legislative session begins.

Many advocates are still pushing for Michigan to add more counselors to its public schools. The state reported last year it added over 1,300 mental health professionals to schools since 2018, but it’s still short of the average student-to-counselor ratio recommended by the American School Counselor Association.

The 2024 school aid budget includes $33 million for school-based health centers and another $45 million to upgrade existing centers. Watch for the impact of that spending to appear this year.

DPSCD is set to open a total of 12 high school-based health hubs over the next three years with $4.5 million in philanthropic grants. Some of the hubs have already opened, offering medical, dental, and mental health care.

Special education: How will the state deal with staffing shortages?

School staffing shortages have been a problem in Michigan schools for years, and they’re particularly pronounced in special education. The state’s list of critical shortage areas for schools includes special education administrators, teachers, and support staff in every disability and role. These shortages can make it difficult to comply with state and federal rules on serving students with disabilities.

Much of the discussion regarding special education shortages has been focused on teachers, and not as much on the support staff whose roles are critical to ensuring that students are evaluated and receive the services they are entitled to. This was highlighted during a meeting of the Detroit school board last month, when a handful of special education support staff urged board members to address the shortages they say have led to increased caseloads.

How schools address shortages in special education and other areas is critical to ensuring that students receive a quality education. Though many efforts are underway to address the problem — including training programs that give aspiring teachers a quicker route to the classroom and programs that aim to get high school students interested in teaching — they won’t provide the solution schools and students need now.

MiLEAP: New agency will take on some education functions

Whitmer in July issued an executive order establishing the Michigan Department of Lifelong Education, Advancement, and Potential, which focuses on improving educational outcomes for students in preschool through postsecondary programs. Michelle Richard, who was the governor’s senior education adviser, will lead the department, known as MiLEAP.

With the new agency under a cabinet-level leader, the governor’s office will be more directly accountable for educational performance in the state. That is something critics of the state’s current system have demanded for years. Some education stakeholders hope this will allow the governor to make faster changes in education policy.

The department moves forward in 2024 with work on issues such as child care licensing, before- and after-school programming, and college scholarships. Meanwhile, educators, administrators, and policy makers will be watching whether MiLEAP leads to more efficiency or more bureaucracy.

The department is made up of three offices: early childhood education, higher education, and education partnerships. It takes over several functions previously handled by the Michigan Department of Education, including the Office of Great Start, which serves the educational needs of children up to age 8.

‘Right to literacy’ settlement: How will DPSCD allocate $94.4 million?

DPSCD has a big new pile of state money to help address problems with reading and literacy for students in the district, thanks to a settlement in the 2020 “right to literacy” lawsuit.

The state appropriated $94.4 million under the settlement, and DPSCD has until 2027 to spend the money. But big decisions will come this year on how the money can best be used to improve student achievement.

A task force is working on recommendations to the district on how to spend the money, based on community input. Its recommendations are due by June 30. The district doesn’t have to adopt the recommendations, but Superintendent Nikolai Vitti has said the district will consider them.

District officials have been previewing their own ideas for how the money might be spent, including hiring more academic interventionists, increasing literacy support for high school students, and expanding teacher training on how to help students who are several grades below reading level. At a school board retreat in November, school board members brainstormed solutions that included training high schoolers to teach basic reading to young children, and partnerships with maternal health programs and early childhood centers to help educate families about literacy before their children enter school.

One thing to keep an eye on is whether the solutions meet the terms of the legal settlement requiring that the money be invested in programs that follow evidence-based literacy strategies. The money can also be used to reduce class sizes for K-3 students, upgrade school facilities, and provide students with more reading materials.

School safety: Proposals respond to Oxford killings

Legislation and reform aimed at preventing school shootings will remain a top priority for lawmakers in 2024.

Since the Nov. 30, 2021, shooting at Oxford High School, where a 15-year-old killed four students and injured seven others, Michigan has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into improving school safety.

The 2024 school aid budget allocated $328 million to improving student safety and mental health.

Numerous bills addressing school safety were also introduced last year, including one that would mandate that all school buildings be equipped with panic alarms, one that would create a state office of school safety, and one that would require an emergency safety manager in each district.

In November, Snyder, the State Board of Education member, proposed a resolution calling for stricter safety training requirements for school staff and increased accountability for school employees and administrators for safety lapses. The proposal came after an independent report on the Oxford H.S. shooting found multiple failures by school administrators to take steps to prevent the killings.

The board didn’t adopt the resolution, but many members expressed interest in revisiting it after more input from state officials.

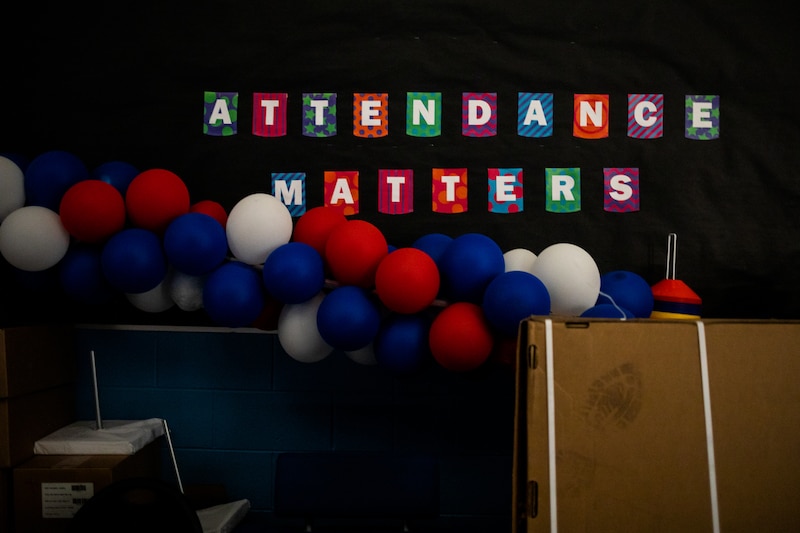

Chronic absenteeism: Will schools succeed in improving attendance?

Last year brought some encouraging news with small declines in chronic absenteeism. But even with those dips, large numbers of students in the Detroit district and across the state are missing far too much school.

We’ll have our eye on this issue, because efforts to improve student achievement won’t work when classrooms are missing students on a regular basis, and teachers are constantly having to reteach material that students missed.

Chronic absenteeism is defined as missing 18 or more days in a school year. During the last school year, nearly 31% of Michigan students were chronically absent. In the Detroit Public Schools Community District, the rate was 66%.

Important issues to watch in 2024: Will schools find innovative ways to improve attendance? What happens to students whose frequent absences trigger punitive acti on? And will communities band together to address the causes of chronic absenteeism?

Hannah Dellinger covers K-12 education and state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at hdellinger@chalkbeat.org.

Lori Higgins is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at lhiggins@chalkbeat.org.