Detroit Superintendent Nikolai Vitti sees the school buses rolling down the streets of Detroit, transporting students he doesn’t serve to schools he doesn’t lead. It’s hard to watch, given the difficult decisions Vitti has had to make in the last month to delay the return to in-person instruction.

“Every time I have to make these decisions, I lose a piece of my professional soul because it’s not always the right decision for kids, because you can’t get it completely right, because there are still families that just want online learning and there are still kids that want to stay home and learn from home.”

Like some big city school districts in the U.S., the Detroit Public Schools Community District had to grapple with community infection rates of 30%-40% at the beginning of the year, when students were set to return from winter break. But while students in New York, Newark, Philadelphia, and beyond have returned to face-to-face instruction in the midst of an omicron-fueled surge, Detroit kids have remained at home, learning online since Jan. 6.

Detroit isn’t the only Michigan district where students have been stuck in remote learning all year. Flint Community Schools announced last week that it would extend remote learning “until further notice.”

Across the nation, most schools have returned to in-person learning following the winter break. But chaos has ensued. Some schools have had to shut down because so many teachers and students were out sick. In Chicago, there were public battles between administrators and union leaders that cancelled classes for days. The surge has forced some school districts to strengthen their COVID protocols, including in Los Angeles, which told students over the weekend they must now wear surgical or higher quality masks, rather than cloth masks.

Taylor Johnson-King, a senior at Cass Technical High School, supported the switch to virtual learning in January. She, too, was worried about high infection rates in the city and felt a delay would give the numbers a chance to drop.

But the extended remote instruction is starting to take its toll on her and others. Attendance has been down on a number of days, and there’s been extensive research that illustrates that remote learning isn’t the best for all students.

“I wanted to go virtual because of the cases, and I had already prepared myself. But I don’t know if I prepared myself enough for this,” Taylor said.

In Detroit, the biggest pressure has come from some vocal employees and families advocating to shut down buildings they believe aren’t safe. Ultimately, Vitti says the city’s high case numbers and low vaccination rates would have made running in-person schools impossible this month.

“Knowing all of the factors that needed to be weighed and considered, I know I made the best decision to postpone an in-person learning return after winter break and I hope I do not have to make that decision again,” Vitti said. “Someone loses every time I do. It was the best overall decision for DPSCD.”

In Detroit, while 80% of district employees are fully vaccinated, just 38% of city residents are fully vaccinated. Among those, 5% of 5-11-year-olds have been fully vaccinated. Twelve-to-15-year-olds are 22% vaccinated. Twenty-eight percent of 16-19-year-olds have been fully vaccinated.

The contrast between Detroit’s vaccination numbers and those in some other big cities is stark. Take New York City, for instance, where 74% of residents are fully vaccinated, including 33% of 5-12-year-olds and 75% of 13-17-year-olds. Schools there fully opened after winter break.

Many other communities have much higher vaccination rates, particularly for children. In Newark, 58% of 12-17-year-olds are fully vaccinated. In Kansas City, 33% of children 5-17 are fully vaccinated, and in St. Louis, the percentage for 5-17-year-olds is 35%.

Vitti said the vast differences in vaccination rates means it’s impossible to adequately compare Detroit with other school districts and their decisions to reopen. The low vaccination rates are a problem for a number of reasons. Those who are unvaccinated are more likely to be infected, and more likely to have more serious illnesses as a result of infection, Vitti said.

Vaccination rates will almost certainly remain low on Jan. 31, when students are set to return to the classroom. But the district will have a new key strategy in its efforts to reduce COVID spread: a COVID testing requirement for students. Students whose parents don’t consent to weekly, mandatory testing will automatically be transferred to the district’s virtual school.

In addition, a mandate for employee vaccinations goes into effect Feb. 18, and the district is considering a vaccination mandate for students. Vitti has been vocal on the latter issue, urging state officials to require student vaccines or “get out of the way” of districts that want to move in that direction.

The low vaccination rates and high infection rates in the city in early January meant the district “would not have been able to manage the amount of inevitable positive cases” that would have led to staff absences, student absences and operational disruptions, Vitti said. He compared it with the struggles airlines had before winter break, saying, “if you don’t have pilots, if you don’t have flight attendants, you can’t fly planes.”

“So, for a school, if you don’t have custodians, you can’t clean. If you don’t have your cafeteria staff, you can’t cook food. If you don’t have noon-hour aides, you can’t supervise students in the cafeteria. If you don’t have security guards, you don’t have people to monitor students as they move to and from class. Most importantly, if you don’t have teachers, you can’t have in-person instruction.”

‘Vast majority’ of big city schools are open

Bree Dusseault, who leads research at the Center for Reinventing Public Education on how COVID is affecting student learning, said schools across the nation are struggling with how to operate and keep classrooms staffed in the midst of the latest surge.

The Seattle-based organization’s ongoing analysis of 100 large and urban U.S. districts has found “the vast majority of schools are staying open.” Detroit, she said, is the only district in the analysis that has been remote since January.

For those that have remained open, the disruptions caused by COVID in January raise questions about how much students are learning and “whether the quality of that learning experience would be equal to in-person learning in December or November,” Dusseault said.

She said she understands the complex issues facing districts in cities like Detroit that were hit hard in the early days of the pandemic and are still experiencing the aftershocks.

“To some degree Detroit is actually responding to its very local context. I do think a lot of communities were hit hard. But the way that gets … processed in a family, in a community is different from place to place,” Dusseault said.

Even before the high infection rates in January led to a delay, the district had shifted to remote learning on Fridays in December because of staff and parent concerns about rising COVID cases and the cleanliness of buildings.

The extended remote learning is starting to wear on Ausar Inaede, a senior at Renaissance High School.

“When you’re on the computer, the energy is dead,” said Ausar, who struggled with online learning last school year. “You can’t just go up to your teachers and ask them questions and they’ll help you out.”

Chaos for schools across the U.S.

Infection rates in the city have declined since the first week of the year, to about 25% last week, Vitti said. That’s still far above the 8% rate the city saw in December. Vitti is hoping the rate gets to between 10% and 20% by Jan. 31, when students are scheduled to return to school buildings for the first time since Dec. 16.

“It’s allowing the number to go down a little bit more — and the trend is moving in that direction — and it’ll just lead to fewer positive cases, not an elimination of positive cases,” Vitti said.

A number of districts have reopened in these conditions. But the COVID surge has created chaotic conditions. In Michigan, some districts, including Beecher and Tecumseh, have suspended in-person classes for days or a week because there have been too many student and staff absences due to illness.

Similar storylines are playing out across the U.S. In Philadelphia, the school district has struggled to keep schools open. Earlier this month, more than half of its buildings were shifted to remote learning. Two weeks ago, 15 buildings were closed for face-to-face classes. Monday marked the first day this year that all schools were open for face-to-face learning.

The district’s leadership has asked families to be flexible and prepare for the possibility of a switch to remote learning at any time. But some teachers have complained that the sudden switches from in-person to remote learning make it difficult to plan lessons and teach.

Montgomery County Public Schools, Maryland’s largest district, announced last week it would shift 16 of its schools to virtual learning, “In the interest of the overall school community’s health and safety”

In Oakland, Calif., three schools were closed last week when teachers called in sick en masse. Students also staged a boycott. In both cases, they were protesting COVID safety conditions.

Though New York City campuses have remained open since the return from break, many schools have had acute staffing shortages as well as abysmal student attendance. For the first two weeks following the break, more than 200,000 children each day were out.

Remote attendance a challenge

Despite remaining remote, attendance has been an issue in Detroit. The district has fallen below state attendance guidelines on multiple days during remote instruction. The state requires attendance of 75%. Districts that fall below risk losing some state funding.

LaWanda King, whose three children attend Detroit district schools, has noticed the attendance issue. She makes sure her children are in school every day, even making them wear their school uniforms. But she can see that’s not happening in every home.

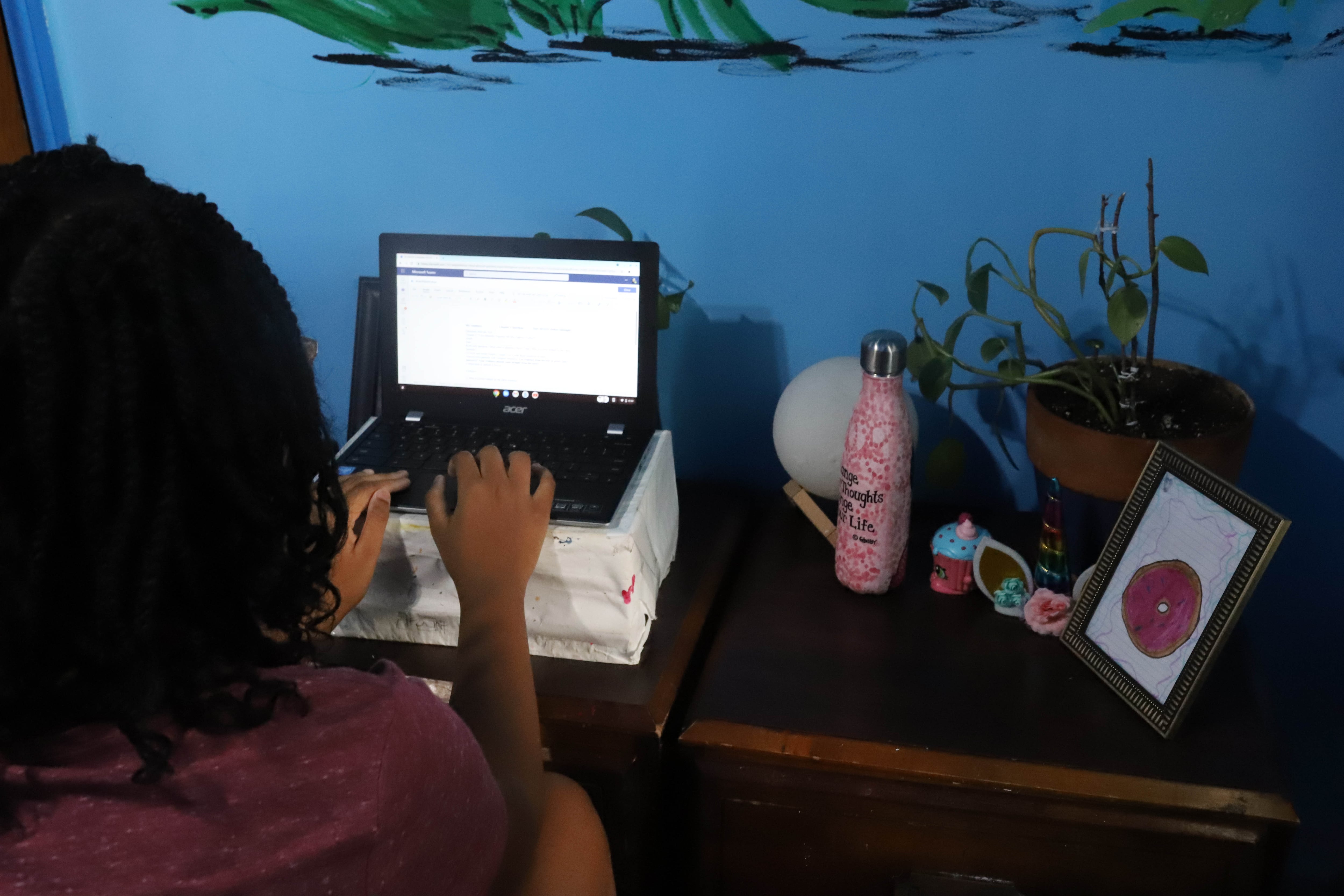

“I’m looking at my son’s classroom because I have [Microsoft Teams] logged in on my phone…there’s only six or seven students in the classroom, and it’s really supposed to be 25 of them in there…so where are all these kids?” she wondered.

“All they have to do is log on and they’re not even doing that.”

She’s not concerned about her children returning to their school buildings later this month because she thinks the safety measures the district has in place — including weekly testing for students and staff — should be enough.

Jan. 31 is the deadline for parents to turn in consent forms allowing their students to be tested for COVID. Those who object or don’t turn in their forms will be automatically transferred to the district’s virtual school, unless they have a religious or medical exemption from the district.

The percentage of children whose parents have consented to the testing has risen from 74% two weeks ago to 90% last week. The goal is 100%. But even then, Vitti stresses that there will be positive cases.

“I think that we will have to become more comfortable with learning center situations in certain schools during certain times,” Vitti said. That means that if there are a large number of teachers absent because of COVID, “we may see students go into an auditorium or go into the media center,” where they can use some online learning programs.

“There’s a benefit to that, versus students not having access to school.”

Chalkbeat staffers Johann Calhoun, Catherine Carrera, and Amy Zimmer contributed to this report.